The internet is an incredible market place hosting millions and millions of software products to make our lives indefinitely easier. To keep up with each other, software grew more and more elaborate in order to provide us customers with lots of different features and services to make us purchase a thing or two. Now due to the resulting increase of complexity we must take special care not to break existing features while developing the next big version. Testing that the next code increment does not break existing stuff is what we testers call „regression testing“, and there is one especially economical way of doing that: test automation.

That’s what we’re going to do today. We gonna test and we gonna automate and we do all that in Python, because with its well-designed concepts Python is suitable for beginners and experts alike. So let’s start!

Shopping list

To start our test automation journey, we will work with the following tools. The versions are the ones I used at the time of writing. I might update them in the future.

- Docker, preferably in its latest version

- Python 3 version 3.10.8

- Firefox Browser 106.0.1

- geckodriver for Firefox 0.32.0

- a Spree Commerce docker image version 3.6.4 as our system under test

(will be pulled automagically in the next step) - Selenium for Python 4.5.0

- unittest as our first test runner (comes with Python 3)

After downloading and installing Docker and Python from their respective web sites, we’re ready to start our system under test.

Deploying the system under test

To achieve this, we simply run the following command:

docker run --name spree --rm -d -p 3000:3000 spreecommerce/spree:3.6.4

If it went well, a quick glance at http://localhost:3000/ should show a shopping catalog page full of cute Rails merch. Now we will prepare and install Selenium.

Installing Geckodriver and Selenium

First we need to download geckodriver that will be responsible for sending our actions to the browser. Please see our shopping list for a download page. Download and extract the appropriate archive and put the extracted executable on your PATH. Please do that in a way that fits your OS and your preferences. I’m a mac user, therefore I move it to /usr/local/bin:

$ mv ~/Downloads/geckodriver /usr/local/bin/

If everything went well,

$ geckodriver -h

should print the version and an instruction page. If not, feel free to drop me a Q in the comments below. Otherwise we move on to installing Selenium.

We will leverage pip3 to quickly go through that step:

pip3 install selenium==4.5.0

Now we’re all set. Let’s go headlong into the real trouble.

Test runner boilerplate

First of all, we create the skeleton of our test class. We write a simple Python unittest class that we will fill in with Selenium web test automation goodness as we go further. Our goal is to see the basic structure of a unittest-based automated test case that we will leverage to execute our browser magic. In your favorite project directory, please create a file named cross_tests.py and fill it with the following code. We will talk about the file name a bit later. Don’t worry, it was not a technical decision.

import unittest

# Start with a base class and derive it from

# unittest.TestCase

class TestSpreeShop(unittest.TestCase):

# setUp is executed at the start...

def setUp(self):

pass

# ... and tearDown at the end of each test case.

def tearDown(self):

pass

# This will be our first test:

# We will open the shop's homepage

# and verify that it worked.

# For now, we will just let it pass.

def test_isOpen(self):

pass

# The main entry point of our unittest-based execution

# script. Think of it as an actual main method similar

# to Java's or C's.

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

Great, that almost looks like a real test already. Now finally we are going to open a browser window.

Starting and closing the browser

We write a small support function:

def open_browser(self):

return webdriver.Firefox()

And we apply it in setUp:

def setUp(self):

self.driver = self.open_browser()This opens a Firefox window it its most pure form whenever we execute one of the class‘ test methods. We could configure it further in open_browser, but for our purpose at the moment, this is perfectly fine.

Now before we perform any actions on the page, we must make sure that the browser window is closed appropriately after each test run. In tearDown, we do:

def tearDown(self):

self.driver.quit()Caveat: confusion potential

Selenium’s webdriver has a close()-method, but please always use quit() instead. It takes care of clean browser termination with regards to Selenium’s execution, whereas close() will just terminate the browser causing warnings.

Alright! We have taken care of the browser handling. Time to do stuffs with it.

Opening the landing page

The most basic action ist to open a web page. Thankfully this task is handled by Selenium with a simple one-liner. Given our sample web shop is up and running, we do:

self.driver.get("http://localhost:3000/")We introduce the line to the test case method test_isOpen, which we introduced in our boiler plate. But before we head into executing the test case, we have to be aware of the fact that we as the user can see the page being open, but the computer can’t. We have to programmatically verify that our expectation „landing page is open“ is met.

Verifying the outcome

To do that we verify these 3 conditions:

- the window title contains the landing page’s HTML

title - the most prominent logo exists on the web page and

- it’s actually visible (i.e. it does not have its

displayproperty set tonone).

We add this code directly below the get – line from before:

self.assertTrue("Spree Demo" in self.driver.title,

"'Spree Demo' is not in the browser's title.")

logo_element = self.driver.find_element(By.ID, "logo")

self.assertTrue(logo_element.is_displayed())The first line peeks into the page title, which is another staple of Selenium, and then checks, if it contains „Spree Demo“ with Python’s in-operator. Using unittest's assertTrue, we verify that this is the case, and if not, we print a custom error message. Condition 1 done.

The second line depicts the method you will probably use the most whilst moving forward in your test automation career: find_element goes through the page’s DOM and grabs the element that meets the given criteria. Here we search for an element with the HTML id „logo“. If it fails to find the element, it drops a NoSuchElementError. Therefore, we just implicitly verified condition 2.

The return value is a WebElement object that we can do clicks, inputs and various other actions on. We will use the object’s method is_displayed() to check, if the logo is visible therefore verifying our 3rd condition.

Straight-forward so far. At this point your code should look like that:

import unittest

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

# Start with a base class and derive it from unittest.TestCase

class TestSpreeShop(unittest.TestCase):

# setUp is executed at the start...

def setUp(self):

self.driver = self.open_browser()

# ... and tearDown at the end of each test case.

def tearDown(self):

self.driver.quit()

def test_isOpen(self):

self.driver.get("http://localhost:3000/")

self.assertTrue("Spree Demo" in self.driver.title,

"'Spree Demo' is not in the browser's title.")

logo_element = self.driver.find_element(By.ID, "logo")

self.assertTrue(logo_element.is_displayed())

# Support method. We will use it to open a browser instance in setUp.

def open_browser(self):

return webdriver.Firefox()

# The main entry point of our unittest-based test execution script.

# Think of it as an actual main method similar to Java's or C's.

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

Let’s execute it by doing:

python3 cross_tests.py # Linux or MacOS python cross_tests.py # Windows

If all went well, your console should display a big OK:

➜ pyta_tutorial git:(main) python3 cross_tests.py . ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Ran 1 test in 4.719s OK

Congratulations, you just executed your first Python-Selenium-test:

Our shop’s landing page can be opened and it is displayed correctly.

What is this driver thingy by the way?

Simply put, the driver is the glue between our code and Gecko (or Chromedriver respectively), thus it’s the interface to our browser window. It handles all the requests that we perform like find_element, click, „are you displayed?“, perform key strokes, „grab that text of an element“ etc. pp. Under the hood, Gecko is an http server, which receives requests sent by the driver everytime we perform one of the above actions. The driver then interacts with the browser in the way we tasked it to and sends a JSON-based response object that we can base our future work on. Everything is encapsulated by Selenium so that we can work with simple objects during test automation development without having to deal with HTTP or JSON.

Performing and validating browser actions

Now that we know the basics of how to write automated tests with Python and Selenium, let’s develop a more complex example.

The best candidates for automated tests are cross tests. These are tests that cover representative cross sections of the product. One example could be: Put items into the cart, view the cart page and perform the checkout. This is the reason we named our test file cross_tests.py. It is good practise to start test automation for a new project by coding these cross tests first.

For the sake of brevity here, we will write up the test until the checkout page. The rest is homework. Don’t worry, I got you covered with the full source code in my bitbucket.

Ok, without further ado, here’s the code. Please add the following method to the test class:

def test_findSpreeBagAndCheckout(self):

self.driver.get("http://localhost:3000/")

# Landing and catalog page

self.driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "[href='/t/spree']").click()

self.driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "a[href*='spree-bag']").click()

# Product page

self.driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "input#quantity").clear()

self.driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "input#quantity").send_keys("3")

self.driver.find_element(By.ID, "add-to-cart-button").click()

# Cart page

self.assertTrue("Shopping Cart" in self.driver.title,

"'Shopping Cart' is not in the browser's title.")

self.driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, "img[src$='/spree_bag.jpeg']").is_displayed()

qty_value = self.driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".line_item_quantity").get_attribute("value")

self.assertEqual(qty_value, "3", "The item quantity is not the same we typed in!")

cart_total = self.driver.find_element(By.CSS_SELECTOR, ".cart-total > .lead").text

self.assertEqual(cart_total, "$68.97", "The total cart value does not match our expectations. That's a blocker!")What’s new here?

If we look back at our first landing page test, you will notice that we use a lot of new things. We will cover them one by one now.

CSS selectors

One thing that catches the eye is that we looked for elements by using CSS expressions. You may have heard about them from your frontend peers, or maybe you have even worked with them yourself already. If not, don’t worry. We will cover them in a followup post. For now, I will give you a few translations:

[href='/t/spree']

„Give me a page element, whose attribute href is equal to ‚/t/spree'“. Quick reminder: href is used in link elements for defining the target URL that is opened, when the user clicks the link.

a[href*='spree-bag']

„Give me any link element, whose attribute href contains ’spree-bag‘.“

img[src$='/spree_bag.jpeg']

„Give me an image element, whose attribute src ends with ‚/spree_bag.jpg‘.“

input#quantity

„Give me an input element, whose HTML id is equal to ‚quantity‘.“ Yes, we could have used By.ID with „quantity“ here, but I wanted to be explicit about the element type input.

.line_item_quantity

„Give me an element that has line_item_quantity in its class attribute.“ The leading dot indicates that we are looking for elements that has the specified class. It is roughly equivalent to [class*='line_item_quantity'].

.cart-total > .lead

„Give me any element that has the lead class and that’s preceded by any element that has the cart-total class.“

By using CSS selectors you can be very specific about what element you want to use in your test case. This makes CSS selectors incredibly powerful and versatile while maintaining a solid degree of simplicity, especially compared to XPath (Ugh).

New properties and methods used in our test case

Aside from CSS selectors, we used several new methods and properties in our new automated test.

click() issues a click on the target element. Straight-forward.

.text contains the element’s written text. In <p>Some text</p> for example, we would get access to „Some text“.

get_attribute("someHtmlAttribute") gives us the content of an element’s HTML attribute. In our test we fetch an element’s value attribute that is often used to set the content of an input element. Another example might be the link element we talked about earlier. Given we want to have its href attribute for some further verifications. On our page:

<a id="mylink" href="https://www.example.org">an example link</a>

Then in our test we could do:

target_href = self.driver.find_element(By.ID,"mylink")

.get_attribute("href")

self.do_some_shenanigans_on(target_href)

send_keys("My desired input") imitates key strokes on an element. We use it to type any string we want into our target text input element. In our test, that would be the „quantity“ input box.

And finally, with clear() we have a little helper that clears an input element from any content. In our test we use that to remove the preset value. Otherwise we would accidentally order 31 bags: „3“ from us and „1“ from the value preset by the page.

Continuing from here

Alright, let’s sum up what we accomplished:

We have seen how to open and close a browser window, do various actions on the page, verify their outcomes and finally we used that to write a fairly large cross test. And all of that on a full fledged ecommerce web app. Great job! Now where should we go next? For the next post, as promised, I’d like to go back one step and give you a deeper introduction to CSS expressions, because they will accompany you for a long time during your test automation journey. Afterwards we have to tackle a big problem you probably already noticed:

Copious amounts of repetition.

To tackle that we will leverage Behave, a Behavior Driven Development framework that makes it possible to write test cases in human-readable text form on top of a DRY Python code base. Afterwards we will apply the Page Object Pattern, a test automation – specific design pattern to reduce repetition even more.

Okay. To keep you busy while I am busy, how about finishing the checkout? As a reminder, you can find the full source code in my bitbucket repo. Or you can spoil yourself a little about Cucumber in Rust.

See you in the next post!

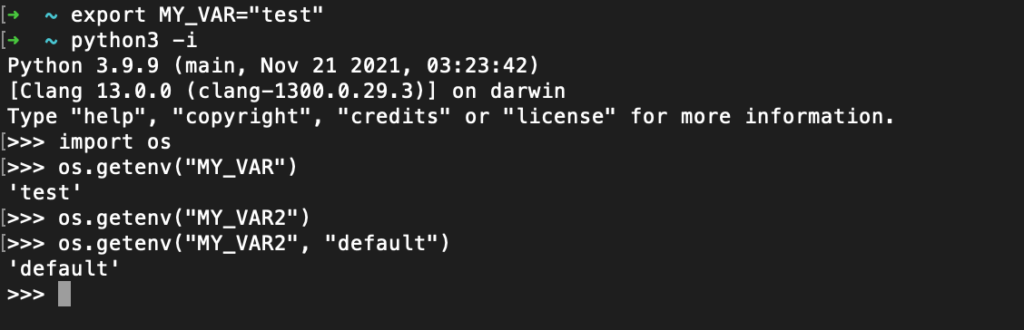

![For python environment variables with os.environ[key], do the following: export MY_VAR="test", python3 -i, import os and os.environ["MY_VAR"]. This should yield 'test'.](https://www.florianreinhard.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Bildschirmfoto-2021-12-23-um-17.29.18-1024x272.png)